3 Things that Happen if the United Nations Disappears Tomorrow

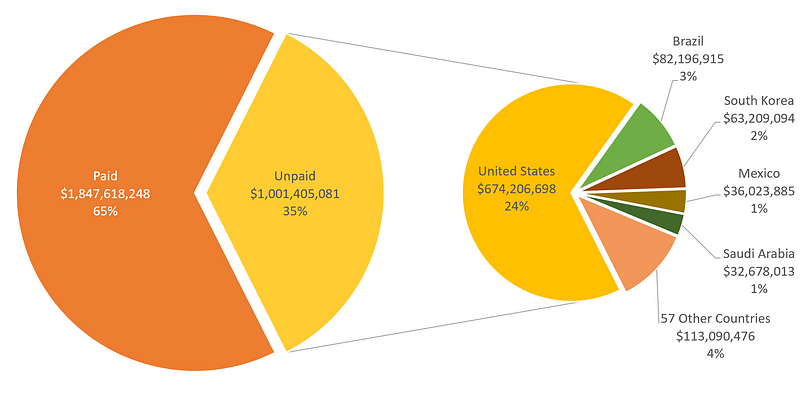

We’ve been warned that the United Nations is facing its biggest cash crisis in nearly a decade, with USD 1.3 billion owed by 62 Member States including the US, Brazil, South Korea, Mexico and Saudi Arabia. Secretary-General António Guterres is warning about the possibility of global disruptions to regular operations and defaulting on staff salaries and vendor payments.

Such news is music the ears of people like former US National Security Advisor John Bolton, Executive Director of UN Watch Hillel Neuer and Queensland Senator Malcolm Roberts — the latter of whom repeatedly calls for Australia to “exit the UN” despite that not being possible.

Pundits wax indignant about the UN being an unelected bureaucratic monolith with no mandate and diminishing relevance in the modern world order. Bolton himself once advanced that if the UN HQ building in New York City “lost 10 stories, it wouldn’t make a bit of difference.”

Just how big a difference would be made if the UN did, so to speak, lose 10 stories? If world leaders were overpowered by nationalist sentiments, ushering an era of realpolitik and isolationism in matters of foreign policy and national security that meant the end of international organisations — what then?

In the spirit of Bolton’s hyperbolic rhetoric, let’s explore the following: if the UN and its various agencies were to disappear overnight, what are some of the immediate consequences?

(1) Millions would starve within weeks

The World Food Programme (WFP) is the arm of the United Nations responsible for delivering emergency food assistance. Every time a parent berates their child for not finishing their dinner, citing the starving children in Africa as justification, someone at the WFP gets a little tingling sensation.

The WFP is an emergency responder, every year distributing more than 15 million food rations to victims of war, civil conflict, drought, floods, earthquakes, hurricanes and crop failures. There are currently six emergencies to which the WFP is responding, including in North-Eastern Nigeria, the Sahel and Yemen. In Yemen alone there are 12 million people who receive WFP support every single month.

There is strong evidence in favour of the effectiveness of the WFP’s role as an emergency food provider. A 2012 study by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development reviewed 52 different evaluations of WFP operations, finding robust positive results on whether the WFP achieves its humanitarian objectives and whether the WFP efforts create positive change. In other words, most studies find the WFP to be an effective organisation at combating hunger and saving lives and livelihoods in emergencies.

Now, let’s assume the WFP ceases to operate. Without their steady flow of food assistance, over 20 million people in Yemen would wake up hungry every day. Add to that the 3 million people in North-Eastern Nigeria who are entirely dependent on food assistance programs, and over 5 million Congolese receiving life-saving food assistance in 2019. These are people whose governments do not have the means to provide assistance and who’d be entirely left to their own devices. This is the immediate short-term impact arising from a complete halt of WFP activities, to say nothing of the WFP’s work with governments to strengthen their capacity and enhance their emergency preparedness.

(2) Civilians would die as civil conflicts intensify

UN Peacekeeping operations (PKOs) are designed to support countries transition from violent conflict to peace. Peacekeepers (aka. the Blue Berets or the Blue Helmets) are deployed to monitor and facilitate the transition processes, protect civilians, restore the rule of law, promote human rights and assist in the disarmament and reintegration of former combatants. There are currently 14 active PKOs, with the two largest ones being in South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Internal civil conflicts can last between 5 to 10 years, and the risk of conflict flaring up again is highest for at least a decade after the conflict ends. Depending on the context, studies show that PKOs can be effective through four different channels:

- PKOs reduce the lethality of ongoing conflicts.

- PKOs increase the chances of hostilities ending.

- PKOs prevent conflict from breaking out or recurring.

- PKOs prevent contagion to neighbouring countries.

By analysing the combined impact of these four channels, a January 2019 study evaluated the effectiveness of PKOs and simulated their potential benefits. PKOs with strong mandates and robust budgets can reduce the risk of major conflicts by about two-thirds. A global two-thirds reduction translates to:

- 150,000 fewer dead people.

- 57,000 fewer dead children.

- 900,000 fewer people without drinking water.

- 1,300,000 fewer undernourished people.

Maybe you don’t trust these numbers. Maybe you don’t trust the motivations of the study’s authors. Maybe you want to point out the time UN peacekeepers stood by and watched the Rwandan genocide, or the multiple instances of sexual abuse at the hands of UN peacekeepers, or the argument that peacekeepers don’t tackle the root causes that brought them there in the first place. Fair enough — Peacekeeping is one of the most controversial subjects about the UN, and peacekeeping efforts are by no means perfect. But no-one can deny that, on the whole, peacekeeping operations save lives. They save lives because they introduce a truly neutral middleman between cocked and loaded weapons. They save lives because some unnoticed conflict in some forgotten part of the globe all of a sudden becomes a matter of international concern with the whole world watching. They save lives because they literally stop guns from firing. These are indisputable facts.

(3) Child vaccination levels would plummet

UNICEF operates globally to safeguard children’s lives and their rights, working with governments to promote child protection, inclusion and survival. UNICEF also provides emergency assistance to ensure child nutrition, shelter and safety.

Most notably, UNICEF is primarily responsible for immunising children in the developing world. UNICEF is the world’s biggest purchaser and distributor of vaccines for developing countries, having purchased nearly 1 billion vaccine doses in 2017. UNICEF alone purchases and distributes over 85% of vaccines for all of Africa, and is responsible for one-third of global vaccine purchases. That’s right, one-third of the world’s vaccines are purchased by a single organisation. And that’s not all — UNICEF vaccinates 45% of the world’s children under 5 years old.

As a central procurement organisation for developing countries, UNICEF is able to act as a collective bargainer and negotiate with vaccine manufacturers on a level playing field. Moreover, by representing a significant portion of the market for vaccines, UNICEF is able to flex its price-setting muscle. Since 2013, the prices for tuberculosis vaccine and polio vaccine purchased by UNICEF have decreased by 11% and 54% respectively. Across 11 different vaccines, UNICEF pays a median price of USD $0.25 per dose while self-procuring countries pay a median price of USD $4.79 per dose — almost 20x more expensive.

Remove UNICEF from the equation and not only does the burden of immunising half the world’s children fall back on the developing world, but it suddenly becomes an unwinnable battle as price-setting power reverts back to vaccine manufacturers.

I’ll never deny that there is significant room for improvement at the United Nations. As ultimately a taxpayer-funded organisation, I have high expectations of the UN and I’m unsettled when those expectations are not met.

In saying that, my expectations are also realistic — I don’t expect the UN to be the world’s Superman and fix all our problems. Anybody that sees the UN as the be-all and end-all of humanity’s challenges is naïve and should be reminded of UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld’s famous remark:

“The United Nations was not created to take mankind to heaven, but to save humanity from hell.”

Equally as naïve, however, are those that believe the UN to serve no purpose other than providing cushy and overpaid jobs for tree-hugging, globalist, farmer-hating, open-border-loving, private-property-stealing, holier-than-thou, virtue-signalling Chardonnay socialists.

The United Nations is critical to the survival of millions of people around the world. If it didn’t exist, we would have to create it.

Originally published on my Medium page, which I no longer use.