Why the Taliban will need to be different this time — in 3 charts

On Tuesday, 7 Sept, the Taliban announced the first members of a caretaker Afghan government to lead the country into an undoubtedly tumultuous future.

For all their nice polished press conferences and pledges to form an “inclusive” government, there’s absolutely no reason the Taliban will be different unless they need to be different. Analysts say this will partly depend on external forces and macro-level issues, such as trade with Russia and China and the Taliban’s ability to do the big stuff of sophisticated governments (e.g. tackling droughts).

What about simpler factors? What if we look inside the country? Afghanistan's realpolitik is very different from what it was two decades ago. To assume that the return of the Taliban means a return to late 90s Afghanistan is a mistake that fails to consider three crucial realities alive in the Afghanistan of 2021.

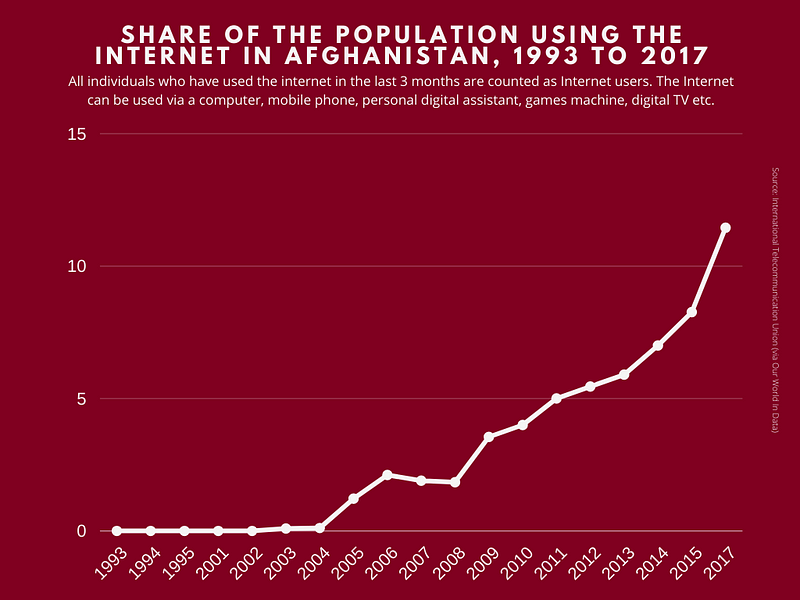

1. The internet arrived in Afghanistan

It’s easy to forget the sheer state of underdevelopment in which Afghanistan found itself back in the 1990s. Admittedly, the advent of the internet took everyone by storm back then, but its proliferation in Afghanistan is a direct consequence of the US reconstruction efforts.

Afghanistan went from nearly universal internet disconnection to over 4 million consistent internet users. Mobile phone usage saw a similar increase — going from near zero to over half the country now having a mobile phone subscription.

The Taliban cannot put this genie back in the bottle. This is a reality with which it will have to live and to which it will have to adapt. Much like the printing press supercharged the Protestant Reformation, the internet creates a serious risk of popular dissent for the Taliban. Millions of people with internet access will mean millions of people who will question your rule.

Sure, the Taliban could simply shut down or filter the internet when things get too hairy. This happens all the time in the region. But the fact remains that, no matter how many times governments around the world shut down the internet, they always have to turn it back on. This will be a concession with which the Taliban will need to come to terms.

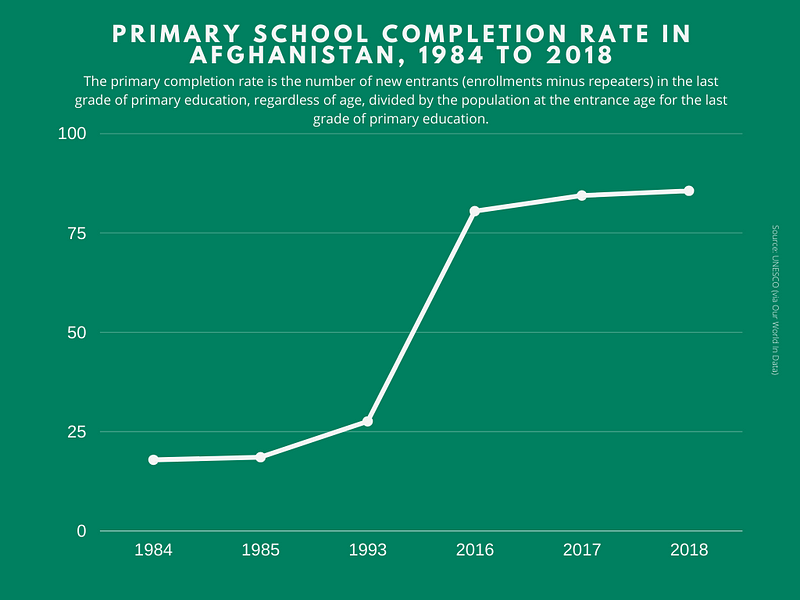

2. Generations of children grew up in an inclusive society

From the very beginning, the Taliban pledged to respect women and the rights they gained over the past 20 years. Pretty much no-one believes them. To a certain extent, however, the Taliban might not have much of a choice on the matter.

One of the biggest successes in Afghanistan over the past 20 years has been the increase in primary school enrolments and completion rates for both girls and boys. Today, over 85% of children complete primary school, in comparison to 28% under Taliban rule in the late 90s. 67% of girls are completing primary school, which admittedly is less than the percentage of boys but it’s more than 0% under Taliban rule.

There are obvious benefits from this, like increased levels of literacy and the opportunities presented from increasing women and girls’ education and participation in the economy. At the end of the day, societies that treat women badly are poorer and less stable.

Importantly — generations of children spent their most formative years under a co-ed system, especially in key urban areas like Kabul. The Taliban missed their opportunity to feed them fundamentalist dogma and indoctrinate them. These children are tomorrow’s elders and middle class, and they won’t identify with Taliban hardliners. The Taliban will need to adapt.

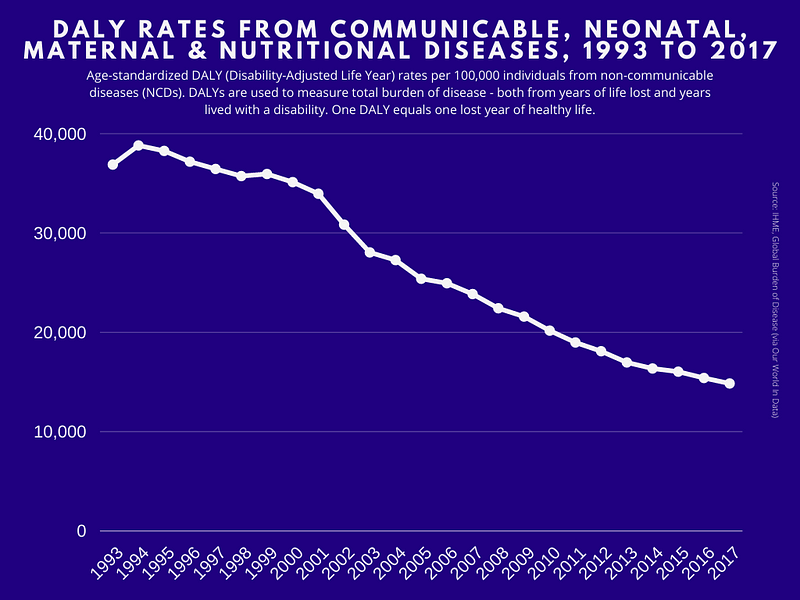

3. People live better lives today than they did under Taliban rule

The undeniable fact about Afghanistan is that despite its rampant corruption and worrying development indicators — the country is a better place than it was 20 years ago.

Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) is a metric that combines years of life lost due to premature death and years of life lost due to time lived in less than full health. It measure’s a population's overall burden of disease, where 1 DALY = 1 lost year of healthy life.

Due to a variety of factors, including better food security and access to drinkable water, people in Afghanistan today die less needlessly than they did in the 1990s. Specifically, we’ve slashed by half the number of DALYs lost in Afghanistan: from almost 40,000 in 1994 to approximately under 15,000 today.

Achieving this wasn’t easy, and maintaining it will be the Taliban’s biggest challenge. Not only does the Taliban lack the technocrats necessary to govern complex economies, but it will also face a hyper-cautious international aid and financial system in the immediate term and an Iran-like, stymied future in the medium term.

All in all, Afghanistan under Taliban rule will not be a kitten- and fudge-based democracy. It will also not be a return to the 1990s injustices and backwardness that are still seared into the world’s collective memory. It will be something in between — a compromise between values and on-the-ground realities which the Taliban will be forced to make.

Originally published on my Medium page, which I no longer use.